Javascript Runtime

An introduction to Javascript Runtime

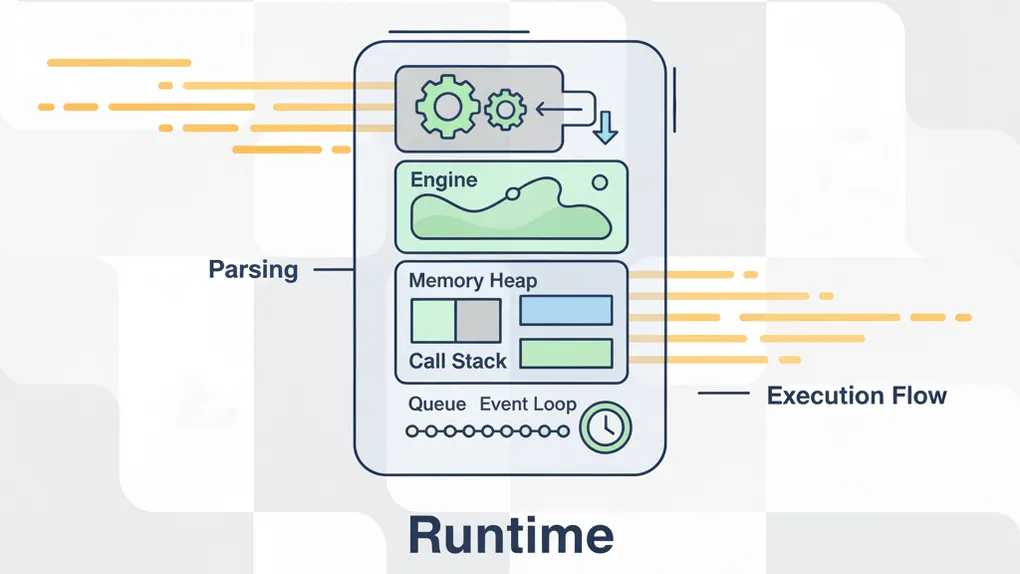

Javascript Runtime refers to the environment where Javascript code is executed, encompassing various components that work together to enable functionality. Central to this is the Javascript Engine, which interprets and executes code But the engine alone isn’t enough. In order to work properly, we need Environment APIs ( Web API for browser and NodeJs API for server) to essential APIs for interacting with the browser or server.

Javascript Engine

The Javascript Engine is a critical component of the Javascript runtime, consisting of several core elements that work together to execute code effectively. The main components include the Call Stack, Heap, Parser, Interpreter, and Compiler, which collectively facilitate the execution of Javascript applications.

Flow of Javascript Code Execution

Parser

The Parser is the first component of the Javascript Engine that processes the raw source code.

During this stage, the parser reads the Javascript code and checks it for syntax errors. If the code is syntactically correct, the parser converts it into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

The AST is a structured representation of the code that highlights the hierarchical relationships between various elements, such as functions, variables, and expressions. The AST enables the engine to understand the code’s intent and flow without concerning itself with syntactical details. It provides a simplified view of the code, which the interpreter will use for execution.

Below is the AST of const a = 'hello world'. You can tryout and explore AST with this playground

{ "type": "Program", "start": 0, "end": 23, "body": [ { "type": "VariableDeclaration", "start": 0, "end": 23, "declarations": [ { "type": "VariableDeclarator", "start": 6, "end": 23, "id": { "type": "Identifier", "start": 6, "end": 7, "name": "a" }, "init": { "type": "Literal", "start": 10, "end": 23, "value": "hello world", "raw": "'hello world'" } } ], "kind": "const" } ], "sourceType": "module"}Once the AST is generated, the Interpreter takes over to execute the code.

The interpreter translates the AST into intermediate machine code, which is a lower-level representation of the code that the computer’s processor can execute. This process involves traversing the AST and invoking operations as dictated by its structure. While the interpreter allows quick execution of code, it may not apply optimizations that enhance overall performance. Consequently, the code runs as is, without taking full advantage of optimization opportunities inherent to the underlying machine.

To address the performance limitations of the interpreter, modern Javascript Engines implement a Just-In-Time (JIT) Compiler.

JIT - Just-In-Time Compiler

JIT compilation occurs during the execution of the program, converting frequently executed sections of code (often referred to as “hot” code) into optimized machine code. This optimized code can be stored and reused for subsequent calls, significantly reducing execution time compared to interpreted code.

By combining interpretation with JIT compilation, engines strike a balance between fast startup times and efficient long-term execution.

Call Stack

The Call Stack is a last-in, first-out (LIFO) data structure that tracks active function calls and manages execution contexts. When a function is invoked, a new frame is added to the top of the Call Stack, containing information about the function’s execution, such as parameters, local variables, and the return address. As functions complete execution, their frames are popped off the stack. This mechanism ensures that control returns to the correct location in the code after a function finishes. The Call Stack interacts with the heap when functions need to access objects or data stored there during execution.

Heap

Unlike the structured Call Stack, the heap is an unstructured space where objects, arrays, and data structures are stored. When the engine needs to allocate memory for complex or variable-sized data, it utilizes the heap. Efficient memory management in the heap enables Javascript to handle the dynamic nature of web applications, which often require frequent creation and deletion of objects.

Example and Illustration

Consider the following Javascript code:

function greet(name) { return `Hello, ${name}!`;}

function welcome() { const message = greet("Alice"); console.log(message);}

welcome();Execution Flow:

- Call to

welcome(): A frame forwelcomeis added to the Call Stack. - Call to

greet('Alice'): Withinwelcome,greetis called, pushing a new frame forgreetonto the stack. - Return from

greet: After constructing the greeting, control returns towelcome, and its frame is executed to log the message. - End of Execution: Once

welcomecompletes, it is popped from the stack, marking the end of the program.

In this illustration, the flow of execution and how the Call Stack manages function calls and returns is represented clearly. Understanding the role of the Call Stack and the overall process of the Javascript Engine is essential for building efficient applications and optimizing performance in Javascript.

JS Environment

The runtime environment provides built-in APIs and functionalities that allow Javascript to interact with the browser or server environment, handling tasks like DOM manipulation, making network requests, and accessing other system capabilities.

Browser Environment

When users interact with the UI, the Javascript Engine often needs to handle user interaction requests via Web APIs, such as:

- DOM Manipulation: Javascript can access and modify the HTML structure and styles of a webpage, allowing for dynamic content updates and interactive user experiences.

- Event Handling: Javascript can listen for user events (like clicks, keyboard presses, and mouse movements) and execute corresponding functions in response.

- Making Network Requests (AJAX): Javascript can asynchronously fetch data from a server without reloading the webpage, enhancing user experience through dynamic content updates.

Unfortunately, the Javascript Engine itself does not inherently recognize these interactions. Instead, it provides a full set of data types, operators, objects, and functions specified in the ECMAScript standard. These features are ultimately utilized by the Web APIs to facilitate dynamic and interactive experiences within the browser.

Server Environment

In a server environment, such as Node.js, Javascript also interacts with various server-specific functionalities to handle incoming requests and perform backend operations. When users initiate actions that require server interaction, the Javascript Engine processes these requests through APIs available in the server environment (like file system access and database connections). Just like in the browser context, the Javascript Engine relies on the same standard ECMAScript constructs to enable effective execution of tasks and resource management by server APIs.

Callback Queue (Tasks, Microtasks, and Event Loop)

In web development, concurrency issues can arise when multiple operations need to occur simultaneously or when asynchronous tasks are handled. For example, user interactions, network requests, and timer events can introduce complexity if not managed properly, leading to problems like race conditions and inconsistent application states.

To simplify these concurrency issues, JavaScript was designed as a single-threaded language. This means that at any given moment, only one unit of work is processed in the call stack. Importantly, each unit of work in the call stack cannot be paused or resumed; it must complete before the next task can be handled. This design choice helps eliminate many common problems associated with concurrency but also presents challenges when trying to manage multiple asynchronous operations effectively.

To address the need for handling as many asynchronous operations as possible without blocking the main thread, JavaScript employs a queuing mechanism, which uses Tasks, Microtasks, and the Event Loop to efficiently manage and prioritize the execution of these operations.

Tasks

Tasks (also known as macrotasks) represent long-running operations or those involving I/O requests, such as:

- Functions executed by

setTimeout - Network requests (e.g., fetching data from an API)

- Event callbacks triggered by user interactions (clicks, keyboard inputs)

These Tasks are placed in the Task Queue, managed by the Event Loop, which ensures that the Javascript engine remains responsive to user interactions. Because tasks must be executed in the main thread, it is crucial that each task completes its execution in sequence. Once the Call Stack is empty, the Event Loop pulls the next Task from the queue and pushes it onto the Call Stack for execution.

Microtasks

Microtasks are special tasks designed to run immediately after the currently executing task, before any subsequent tasks from the Task Queue. Common examples of Microtasks include:

- Promise resolution callbacks

- MutationObserver callbacks

Microtasks are placed in a separate Microtask Queue, which has a higher priority than the Task Queue. This means that after the main task finishes execution, the Event Loop will first complete all Microtasks in the Microtask Queue before moving on to the next Task. This prioritization allows for quick responses to promises and ensures updates occur quickly, maintaining a smooth user experience.

Event Loop

The Event Loop is the mechanism that governs the execution of tasks and microtasks. It continuously checks the status of the Call Stack and the Task Queues, ensuring that execution flows smoothly and efficiently:

- The Event Loop verifies if the Call Stack is empty.

- If the stack is empty, it processes all pending Microtasks in the Microtask Queue first.

- Once all Microtasks have been executed, the Event Loop retrieves the next Task from the Task Queue and places it on the Call Stack for execution.

This cyclical checking process allows Javascript to manage asynchronous operations seamlessly, ensuring that the application remains responsive even during heavy execution loads.

Example

Code

function fnc_resolve1 (response) { if (!response.ok) { throw new Error("Network response was not ok"); } return response.json();}

function fnc_resolve2 (userData) => { // Use a microtask to process the fetched user data processUserData(userData);}

function fnc_reject(error) => { // Use a microtask to log exception console.error("Error fetching user data:", error);}

function fetchUserData() { console.log("Fetching user data");

// Simulate a network request to fetch user data from an API (Microtask) const userRequest = fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users/1") .then(fnc_resolve1) .then(fnc_resolve2) .catch(fnc_reject);}

function processUserData(userData) { console.log("Processing user data"); // Simulate processing of user data console.log(`User Name: ${userData.name}`); console.log(`Email: ${userData.email}`);}

console.log("Start");fetchUserData();console.log("End");Flow chart

Explanation of the Flowchart

- Start: The execution begins with a call to the main function.

- Call

fetchUserData(): The functionfetchUserData()is invoked. - Log Message: The message “Fetching user data…” is printed to the console.

- Initiate Fetch Request: A fetch request is initiated, which gets added to the Task Queue.

- Check Fetch Status: After the fetch resolves, the program checks if the response is OK.

- If the response is OK, the process continues through

fnc_resolve1(), where response.json() is called. - If the response is not OK, an error is thrown, which triggers

fnc_reject(), logging an error message.

- If the response is OK, the process continues through

- Process User Data: Once the data is fetched and resolved, control moves to

fnc_resolve2()to process the user data. - Log Processing: The data is logged, including the user’s name and email.

- Finish Processing: After all logs are executed, processing is complete.

- End: The program execution reaches the end after handling the successful fetch or any errors.